The following article, published in TRUE WEST magizine (Feb. 1993), provided the seeds that grew my novel. When you read the novel you might see just how 'seeds' can grow and take on a life of their own.

IKE MALONE

WESTERNER

By Steven D. Malone

Copyright 1993 & 2012

All rights reserved

Ike Malone’s grave is similar to the others in the old Hico, Texas cemetery, just as it is similar to others all over the American West. It lies in stony ground amid windblown grass and weeds in a cemetery that, like the ghost town of Hico, is almost forgotten. The people and the settlement moved off, following the railhead, and now only the gravestones and the brick ruins linger. Ike Malone’s grave however, contains the remains of a true Westerner.

Three times, Ike pulled up stakes and headed west, moving into territories newly opened on the vast American frontier. Each time he cleared the land, built his house, raised children, and helped create towns and churches. Ike faced and survived all the privation frontier life presented, withstanding the affronts of Indians and outlaws.

Born in late 1813 or early 1814, Ike was the last of four children born to Rhoda and Issac Malone. His brothers were David and Thomas; a sister’s name is not recorded. Issac, a veteran of the War of 1812, served in Georgia and North Carolina. The war was barely over and the news of the battle at New Orleans still fresh when Issac died. He left an estate appraised at seven dollars.

The widowed Rhoda hung on alone keeping the family together on land she inherited from her family. The United States census of 1820 for Chester County, South Carolina, lists Rhoda as head-of-household, then a rare distinction for a woman.

The War of 1812 removed the last British influence over lands and Indians outside the original colonies, and Americans felt free to migrate westward. In the Treaty of Doak’s Stand, October 18, 1820, Choctaw Indians ceded the western half of their lands to the United States, and it became part of Mississippi. Rhoda sold her inheritance in South Carolina in 1821 and appeared again as a female head-of-household on the first tax roll of Copia County, Mississippi.

The land around the area is rolling hills and hardwood forests. Ike soon learned to clear land and to farm. He also learned at least enough writing to sign his name. In 1831, Ike met and married his cousin, Pretia Nix, and by 1832 was a head-of-household in his own right.

Ike prospered and he and Pretia had eleven children – Amanda, Manerva,

Martha,

Thomas, Burns, Melissa, Narcisse, John, and Newton; a set of twins died at one day old. He received title to eighty acres on September 27, 1838, in a time of enormous turmoil in Mississippi. The

state was in the midst of a great banking scandal due to failed investments in rail development. The trouble led to a massive depression and wholesale foreclosures for both plantations and poor

farms. During that time, ‘G.T.T.’ (Gone to Texas) began appearing on the backs of foreclosure notices nailed to the doors as people abandoned their homes and headed to the new

republic.

By 1845, discussion in Mississippi of the coming annexation of Texas had so excited the Malone brothers that all three sold their property and went west. David took his family to Bienville Parish, Louisiana, near where his wife’s family lived, while Ike and Thomas bought land in the Mercer Colony in Texas.

The colony’s founder, Charles Fenton Mercer, was the last and one of the most controversial of the Texas empresarios. The empresario system began with the old Mexican policy of granting land to men who contracted to settle a specific number of colonists. Mercer, a Virginia politician, served as a brigadier general during the War of 1812 and helped organize a plan to establish the free state of Liberia in Africa as a ‘home’ for American blacks. He became the last empresario of the Republic of Texas when he persuaded President Sam Houston to grant him a contract on January 29, 1844. The Texas congress repealed all laws authorizing colonization contracts over Houston’s veto on January 30.

Ike received 640 acres and was paying a poll tax as early as 1846. He farmed the acreage and raised his children there for the next seventeen years.

For reasons of his own, Ike moved his wife, four daughters, and his youngest son to the edge of Comanche country in 1863, right in the middle of the Civil War. He had likely heard of the considerable potential out in the grassland in Hamilton County. His brother Thomas had moved there by 1860. Ike’s son-in-law, John Alford, was also in Hamilton County by that time. Alford had arrived with a wagon load of dry goods and opened the first store in the area. A short time later he received permission to set up a post office. As postmaster, he could name the settlement, and chose Hico, after his hometown in Kentucky.

Heading west again would have been a hard decision for the fifty-five year old Ike. The situation in Texas was grim in 1863. Comanches had taken advantage of the withdrawal of federal troops from Texas at the start of the Civil War and had stepped up attacks against whites. Along the ‘Indian front’ organized militia companies patrolled in response to that threat. The Confederacy even offered its Westerners exemption from service in the main theaters of the war if they would stay home and serve in their local defense units. Ike’s oldest son, Burns, refused the exemption, enlisted in the Eighth Texas regiment and marched into Arkansas and Louisiana. Nevertheless, Ike packed up the remaining members of his family and left to put down new roots in Comanche country. He remained on Honey Creek in north-central Texas the rest of his life.

Before 1854, the area was empty grassland atop beds of limestone and crossed by wooded streams. By 1856, eight families had settled there to raise stock and grow a little wheat, corn, and tobacco. They lived in log homes, some with split-log floors and subsisted on the wild deer, hogs, prairie chickens, and turkeys that were plentiful along Honey Creek. When Ike arrived, he started the second store in the settlement and soon followed that endeavor by hauling freight.

Tom Stinett, who moved to the Bosque River just below Honey Creek, described Hico in 1870. ‘There were two small stores in Old Hico when we arrived there, which carried a few supplies. Uncle Ike Malone and Faggard and Day owned the stores…. ‘Rock’ Martin kept a hotel. This hotel consisted of one big log room, with a shed room across the back, and a cabin in the backyard for a dining room and kitchen. Many were the travelers who stopped at this pioneer inn, for it was on the main trail leading to west Texas, and at this time there were many people from the East going West’.

By 1879, Hico boasted eight businesses and other buildings: Ike’s ‘store of general merchandise’ competed with two others; a blacksmith shop; one saloon; a combination horse-powered corn mill and cotton gin; a school building that also served as a church; and a Masonic lodge. The log cabins disappeared and the townspeople built new homes of finished lumber hauled in from Waco, or of the abundant limestone quarried from outcroppings along the creek.

Ike took considerable risks to keep his wagon stocked with a few goods he carried. He made regular thirty-day circuits from Hico to Waco, then to Hamilton and through Comanche back to Hico. From Hico, he hauled beef, hides and sometimes cotton. He returned with lumber, sugar, coffee, salt, gun powder and gun caps, and probably cloth, clothes, and notions for the women. Ike’s was a lonely and dangerous vigil atop a teamster’s wagon in an empty and hostile land.

Though Ike probably used horses to pull his rig, Jacob de Cordova, in Texas and Her Resources, published in 1852, described teamsters like Ike. ‘This wagon business is a great thing in Texas. His wagon is the home of the driver; his oxen feed on the grass; he eats and sleeps at home. He penetrates the most remote part of the State for a consideration. If he cannot get it loaded, he loads it himself. He is free as dirt and cares for nobody. These men form a class by themselves, but with their useful branch of industry are destined to fade away (like the old bargemen of the Mississippi River) when the snort of the iron horse shall awaken the solitude of the prairies.’

In addition to freighting, Ike actively took part in establishing Freemasonry and religion on the frontier. The Masonic Lodge of Texas lists the Old Hico lodge as Number 447 and says that Ike probably transferred his membership there from Mississippi. The Masons considered themselves a civilizing force in the half-wild state and now claim their lodges often appeared before civil government. That was probably true in Old Hico. Texas Masons founded churches, schools, newspapers, and institutions of public services. They were instrumental in the Texas Revolution and claim Texas heroes Jim Bowie, Stephen F. Austin, Sam Houston, William Barret Travis, and Mirabeau B. Lamar as members.

Ike struggled to secure a place of worship for his friends and his clan amidst the trials of post-Civil War Reconstruction and Indian troubles. He was a deacon in Hico’s Mount Zion Baptist Church, and in the winter of 1869 represented the church when he and others in the area sought to form a new association west of the Brazos. Indian raids made meeting in Paluxy, Texas a dangerous undertaking. According to D. D. Tidwell’s A History of the Baptists in Erath County (1937), the representatives of the churches and the traveling preachers kept ‘their pistols strapped to their waists,’ and a delegate had to guard the horses. On Monday morning, the third day of the meeting, word came that raiding Indians had descended upon Paluxy, coming within a mile of the meeting place, and that townspeople were off hunting them. The group of Baptists assembled quickly, guns at the ready, and promised to meet the next year in Hico. They them adjourned to hurry home, ‘not knowing whether their loved ones would be alive to greet them or not'.

The record of Ike’s dealings with Indians is incomplete, as are the records of white-Indian encounters for the entire state. In the ‘Report of Indian Depredations for the Use of the State’s Constitutional Convention Committee of ‘Frontier’’, November 1, 1875, Adjutant General William Steele wrote, ‘This statement based upon the Material in my office, I am aware is very incomplete…. The frontier people after a few reports, which yielded to them no results, have discontinued reporting their losses. The newspapers teem with accounts of raids with their concomitant horrors of which my office has no official information.’

However, it is known that Ike’s son, Burns, just returned from Confederate service, lost his horse to Indians sometime between July 1865 and February, 1867, His name appears on a report of Indian horse thefts that Hamilton County Judge John S White wrote in February 1867.

Indian troubles hit close and hard around Hico in the first two years of Reconstruction. In Hamilton County alone, from the end of the war to July 1867, three people were killed, two wounded, and one child captured and the reclaimed. Four cattle and 215 horses were stolen. During that same period in the seven counties surrounding Hico, thirty-one men, women and children were killed; twelve wounded; fifteen captured, and 1,122 horses stolen. And that list is incomplete. In 1867, Governor James Webb Throckmorton reported that, since the end of the Civil War, Texas has seen, ‘162 persons killed, 43 carried off into captivity, and 29 wounded.

John Alford, Ike’s son-in-law, answered an Indian alarm in the winter of 1864-65. Supposedly chasing Comanche raiders in a heavy snow, he found himself involved in the Battle of Dove Creek, the largest battle fought with the Indians during the Civil War, and one of the bloodiest in all the Indian Wars. He was among some 300 militia under Captain Totten of Bosque County that joined 110 Confederates under Captain Henry Fosset. They found, instead of Commanches, some 1400 Kickapoo under chief No-ko-aht making a peaceful move from Indian Territory to Mexico. The lengthy confused and widespread fight covered several miles of brush and prairie and lasted all day. Nightfall and new snow ended it giving the Kickapoo a chance to move on, though the Texans were in full retreat. Reports say between thirty-six and fifty whites died; Indian losses were much lower.

As a result of such incidents, and without help from the government, white people fled the Texas frontier, completely depopulating several counties. The Malones and their friends, however, stayed forted up in Hico.

Ike and the citizens of Hico gave short shrift to the outlaws so prevalent on the frontier during Reconstruction. Tom Stinnet, who wrote the description of the town in 1870, also wrote of the town’s not-so-law-abiding citizens. ‘At times things go rather rough. Several men were killed while we were there. Father served as justice of the peace from 1872 until he died in 1894. W. H. Fuller was the first deputy sheriff appointed at Old Hico and he and my father were ‘the law’ for a good many years.’ Deputy Fuller’s cousin, Emily, married Ike’s son Burns.

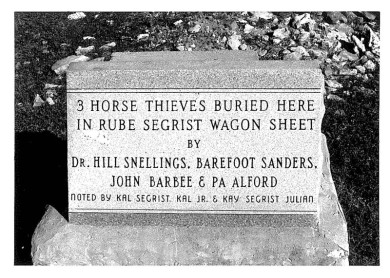

Ike, Deputy Fuller, and the town took care of their own with the usual forms of frontier justice. Once several desperados hijacked Ike’s freight wagon near Iredell at Johnson’s Peak. They stole his team of horses, his money, and his boots. Ike walked barefoot more than ten miles back to town, rounded up a posse, and chased down the bandits near Gatesville. The posse took the men back to Hico and hanged them, then wrapped the bodies in a wagon sheet and buried them in a single grave some fifty feet from ‘respectable people.’ Ironically, the bandits have the best grave marker in the cemetery; it prominently bears the names of the owners of the wagon sheet and of those who paid for the marker.

Ike was robbed at least one other time, late in his life. In late 1878 or early 1879, the aging frontiersman broke his hip in a fall. He was bedridden and his friends and second wife, Eliza Jane, cared for him. Acting on rumors that Ike kept his money hidden in stone jars, three men attacked his house. They forced those present to stand together between Ike’s bed and the fireplace while they threatened and abused the ailing old man. Family legend says that Ike refused to give them any information and told them they could go ahead and shoot him because he would die soon anyway.

Frustrated with the tough old man, the bandits left. Charley Bumpus, the victim closest to the fire, stepped away and found his pants so scorched that they fell off his body. He had been too scared to notice the heat.

When the alarm sounded, the people of Hico rallied and rode down the bandits near Waco. The posse returned the culprits to Hico and locked them in a log shed that served as a jail. In the night when the guards were ‘away eating supper,’ a mob came to the shed and killed the robbers by shooting through the chinking between the logs. Hico citizen s placed the bodies on display for several days so people who came from miles around could ‘view the end of a life of crime.’ The bandits’ take from Ike Malone’s home had been one silver dollar.

Ike made good on his prophecy to the bandits, dying on April 28, 1879, about three months after the robbery. He had survived hardship, war, Indians, and outlaws, but he could not survive confinement to his bed.

Old Hico itself soon died. When the Texas Central Railway Company constructed their line through the north corner of Hamilton County, Ike and the other townspeople accepted the railroad’s proposal to relocate the town some two miles west along the tracks. The first new town lots were sold November 16, 1880. Businesses and dwellings alike quickly moved to the new location. All that remains in Old Hico are the ruins of the old Barbee Mill and a historical marker signifying the existence of a frontier community along the banks of Honey Creek.

When the Daughters of the Republic of Texas honored Ike Malone in 1983, they placed a medallion on his 104-year-old grave. They said of him simply, ‘All bear testimony, Ike Malone, a worthy man.’

Be careful the justice you mete:

(Article given to me by Michael Leamons, City Administrator, Hico, Texas)

A Haunted House In Hamilton County Where Several Men Had Been Killed.

From the Hico Times.

In Old Hico is a house in which, at different times within the past 30 years, some six or seven men have been killed for divers offenses. The house, which is known as “The Slaughter pen,” is situated on the farm of Mr. G. H. Medford, and occasionally some renter moves into it, and also moves out in haste, and the house is rarely occupied it is said the place is frequented by the restless and disembodied spirits of the man whose material existence was so suddenly terminated there, and the result is edifying only at a distance and in broad daylight.

The parties whose mortal coils were shuffled off forgot, on the spur of the moment, to remove their boots, and they therefore, make a great deal of unnecessary noise in their midnight peregrinations, and are anything but seemly and fastidious ghosts. They also seem to be on unfriendly terms with each other, and their bickerings are so open that the neighbors have noticed it and deprecate the lack of secresy that the skeleton in the closet observes. The last addition to this select circle of ghost were two gentlemen who about two years ago, stole some money from old Mr. Isaac Malone.

They were found in a barbershop in Waco and brought back and placed in this house. During the night, while chained together near the fireplace, their spirits escaped to another world. Since then these two ghosts have seemed rather “stuck up" to the other ghosts, probably because they were clean- shaved and wander off to themselves, clanking the chain to irritate the other low-down ghosts. We've noticed that fresh shaved ghost always act this way. The old ghosts retaliate by driving these two away, as, having branded the wrong yearlings only, they cannot associate with ghosts who steal.

Because of these quarrels it is very disagreeable to remain in the house at night.The last occupant moved out two weeks ago, because, as he told Hol Medford, a barrel of pistols had been thrown into the house and all fired off at once; he didn't mind the ghost, but he said the pistols were really dangerous. He was an Englishman and hadn't got the hang of Texas ghosts.

(As reprinted in the Brenham Weekly Independent. Vol. 1, No. 15, Ed. 1, Thursday, April 20, 1882, page 5.)

Note: The Hico Times was Hico’s first newspaper (MWL).

From 'DOCTORS, HEALERS, and HEALTH

The State of Medicine in the Old West:

...reported causes of death included consumption, freezing, fever, pneumonia (these were the four commonest), croup, dropsy, acute diarrhea, cancer, diphtheria, gunshot wounds, cholera, lung fever,

bronchitis, fits (the 10 next commonest), suicide by drowning or poisoning, drowning in a well, dysentery, congestion of the brain, spasms, erysipelas, bilious colic, apoplexy, inflammation of the

liver, and knife wounds. Ten years later the list was topped by diphtheria and consumption, besides "struck by lightning," St. Vitus' dance, teething(!), "kicked by a horse," gravel, worms,

inanition, alcoholism, "struck by a falling body," calculus (presumably not the mathematical kind), scalding, asthma, "gored," sunstroke, hanging (whether official, accidental, or suicidal is

unspecified), heart disease, suicide by hanging, endocesditis, "killed by Indians," and "shot while sparking another man's wife."

William, called 'Burns', contributed his dose to an unnamed California newspaper:

"A SMALLPOX CURE"

By W. B. Malone

To the News: I send the following recipe from a California correspondent, which is said to cure for the dreaded contagion, smallpox: 'I herewith append a recipe which has been used to my knowledge in

hundreds of cases of smallpox. It will prevent or cure, through the pittings or filling.' When Jenner discovered the cow pox in England the world of science overwhelmed him with fame but when the

scientific school of medicine in the world, that of Paris, published this recipe, it passed unheeded. It is as unfailing as fate, and conquers in every instance. It will also cure scarlet fever. Here

is the recipe as I have used it to cure smallpox:

1 gram Sulfate of Zinc

1 gram Digitalis

1/2 teaspoon Sugar

Dissolve in a wine glass of soft water or water which has

been boiled and cooled. Take a teaspoon full every hour.

Either smallpox or scarlet fever will disappear in twelve

hours. For children, the dose must be diminished according

to age. If Countries would compel their Physicians to use

this treatment there would be no need of pesthouses. If you

value your lifer use this recipe."

I'm sorry no date appears on this recipe. I would guess the late 1800's. Smallpox was a deadly disease when it hit the new world. Not only did it kill many whites but it decimated Indian tribes. Burns would appreciate that, in 1994, smallpox has been eradicated from the earth.

(Burn's cure is found in a family history written by his grandson, Ira E. Malone, Jr.)